Shadowy Dragons’ Tails in The Arrival

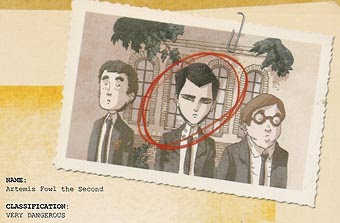

In his New York Times review of The Arrival, Gene Luen Yang mentioned one striking detail of the early scenes: "Shadowy dragons’ tails haunt the Old Country..." But what do those tails represent?

In his New York Times review of The Arrival, Gene Luen Yang mentioned one striking detail of the early scenes: "Shadowy dragons’ tails haunt the Old Country..." But what do those tails represent?

Publishers Weekly said, "Shadowy dragon tails trawl the sky of the man's homeland, suggesting pogrom or famine..." The Washington Post, on the other hand, saw "the dragon shadow of totalitarianism."

Quiet Bubble suggested: The drawing doesn’t want us to believe the city actually swarms with giant dragons--in a later full-page spread, as the wife and daughter walk home to the now-empty house, the tails look like shadows and smoke, which doesn’t make them any less threatening. Rather, Tan’s using fantasy in the right way--as a bravura, overloaded way of conveying symbolically the urgency of real-world terrors and hopes. The family isn’t actually beset by dragons, but oppressive governments and societies sure feel monstrous.

As does war. In calling the book one of 2007's Top Five Children's Books Between Cultures, Mitali Perkins described the story "as a young father escaping an unnamed war-torn country in search of a better life for his family in a new world."

Jetse de Vries at In the Plane of the Ecliptic sees the dragon tails as one of the book's "strong indirect autobiographical hints" that it's the story of artist Shaun Tan's own family, his father having emigrated from Malaysia to Australia.

Finally, Piers Kelly at the Compulsive Reader wrote, "The ambiguous reasons for his departure are suggested by sinister and threatening shadows that swirl like dragons' tails along the empty streets."

My own guess: In the course of the book, Tan has his hero take in the stories of a couple of other immigrants. One has escaped from oppression, the other from a war. Though those episodes are fantastic in their imagery, there's not much room for other interpretations. I suspect Tan wanted to depict all the major aspects of the immigration experience, and I don't see such immediate physical dangers threatening the central man and his family. So I think the dragon-tail shadows represent the threat of want, spurring the man to migrate for new opportunities.

In other words, The Arrival asks us to feel sympathy for not a refugee from violence, but an "economic migrant." That's not so fashionable, so societies create laws against it. But economic migrants are, after all, what most of our own ancestors were.

...turns into a pleasant, helpful pet.

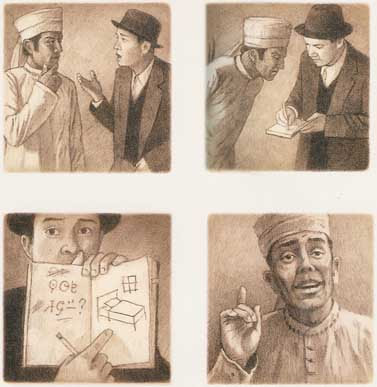

...turns into a pleasant, helpful pet. The pictures then follow a man as he leaves his family and boards a steamship, eventually arriving in a strange harbor.

The pictures then follow a man as he leaves his family and boards a steamship, eventually arriving in a strange harbor.

In fact, out of sixteen page spreads in Chicken and Cat, ten contain words. Some are labels on shops, products, or structures that appear in the scenes (e.g., on the seed packets in the picture above). Others are sound effects and motion labels (e.g., "pat pat pat"), as I

In fact, out of sixteen page spreads in Chicken and Cat, ten contain words. Some are labels on shops, products, or structures that appear in the scenes (e.g., on the seed packets in the picture above). Others are sound effects and motion labels (e.g., "pat pat pat"), as I

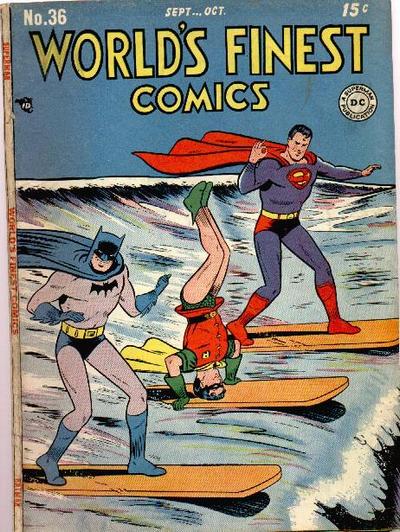

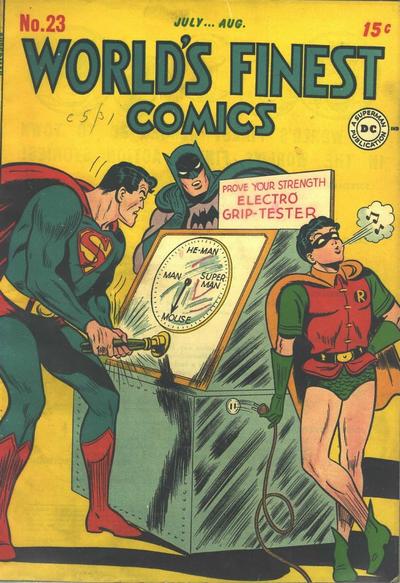

All Golden Age World's Finest covers can be visited through

All Golden Age World's Finest covers can be visited through