Batman, #107 (Apr 1957) contained a story from

Bill Finger and Sheldon Moldoff titled “Robin Falls in Love.” According to the

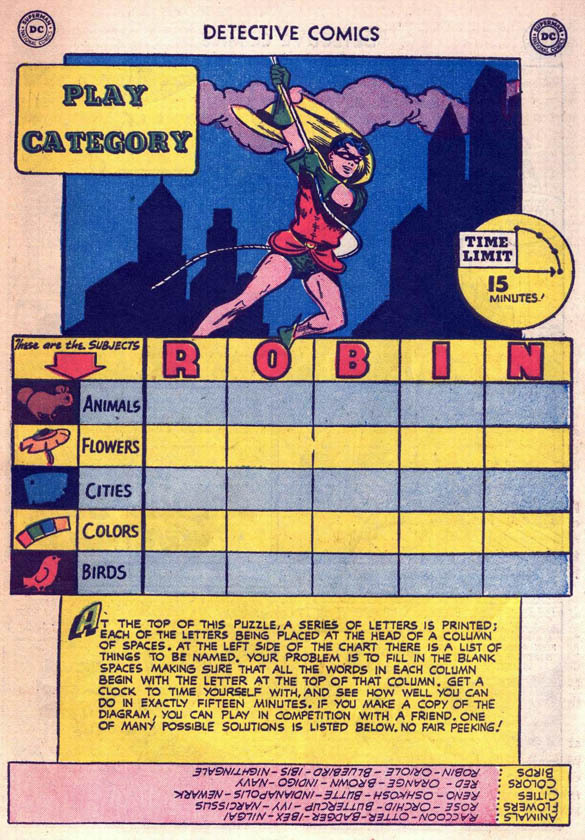

Batman volume of the

Encyclopedia of Comic Book Heroes, this was the first time

Robin the Boy Wonder developed a crush on a girl.

Robin rescues Vera Lovely, a fourteen-year-old figure skater. She kisses him; I haven’t seen the panel in question, but I assume it was an unreciprocated kiss on the cheek. [ADDENDUM: The Robin Appreciation Group on Facebook have kindly

posted that panel, confirming my hunch.] Nonetheless, for a while he’s gaga, with little red hearts orbiting around his head.

But at the end of the story, Robin and Vera agree to be just good friends, and the situation returns to the

status quo ante.

In seven stories of the early 1960s, Betty Kane comes to Gotham and takes up the mantle of Bat-Girl, mostly because she has a crush on the dreamy Boy Wonder. For a long time he doesn’t return her feelings.

In “Prisoners of Three Worlds” (

Batman, #153, Feb 1963), Finger and Moldoff showed Bat-Girl finally getting her wish. The teen crime-fighters share a full-on, lip-to-lip kiss. At the end of the story the young masked couple even goes off together, presumably to do some more necking.

But that’s the pre-“New Look” Dick Grayson. It’s not the Dick Grayson of the 1986-2011 DC Universe. His first kiss appears in the story “Grimm” in

Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight, #149-53. (Since that magazine told stories outside the concurrent Batman continuity, it’s possible that this was yet another version of Dick Grayson, but I’m assuming not.)

In this story, Dick is eleven years old. It’s about a month after he started to patrol Gotham City as Robin the Boy Wonder, about two months after he became Bruce Wayne’s ward. (So much for years of careful training.) Batman and Robin are still struggling to trust themselves as a team and a family.

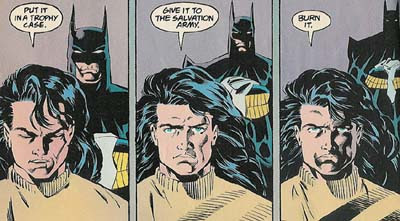

One night Robin chases down a young teen thief called Wily Wendi. She nearly kisses him, as shown in the panel at top, and slips away. After that, Dick can’t get Wendi out of his mind.

He sits in his oddly cluttered room “thinking about

The Girl” and puzzling over “such a strange feeling rippling through me.”

In the adventure that follows, Robin leaves Wayne Manor to go into the underground world of Mother Grimm, where Wendi and other orphaned children live. There are various completely unbelievable twists, spectacularly illustrated by

Trevor Von Eeden and

José Luis Garcia-López.

Von Eeden’s website discusses the background of the story and displays some of the line art.

Mother Grimm’s haven catches on fire. Batman and Robin manage to rescue all the children, with Robin carrying Wendi from a burning hospital. And at last they really kiss.

How do we know that’s this Dick Grayson’s first kiss? Because he tells us (even if he doesn’t admit as much to Wendi).

The story ends with Mother Grimm and her twin sister, both murderous loons, disappearing down a raging river, and Batman having to find new homes for all of the orphans. The whole experience cements Dick’s relationship to Bruce, and his confidence as Robin.

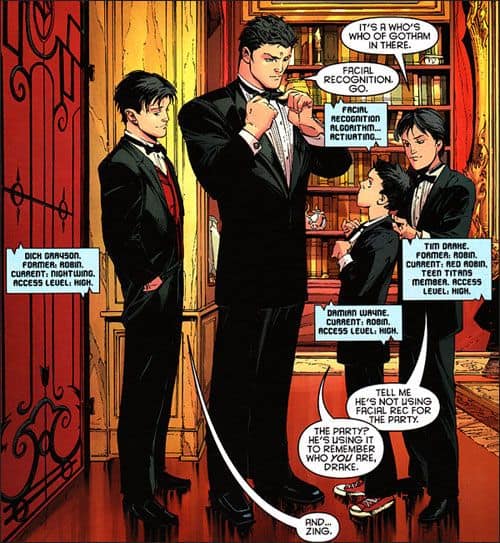

And what about Wendi? Dick, narrating the story in his third Nightwing costume and thus in his mid-twenties, tells us she’s “getting a master’s in journalism.” The art shows us that he keeps tabs on her through the bat-computer. The caption says she’s “just as…memorable” for him as before.

But are they still in touch in any way? Might he run into her in Gotham City, as either Dick Grayson or Nightwing?

J. M. DeMatteis’s script leaves a loose thread just perfect for fanfiction, but I couldn’t Google up a single story about Wily Wendi.

How long will it take now before such a story appears?